Enter Pete Rozelle, 33, who assumed the commissioner post in 1960 and would transform the NFL. By the mid-sixties, thanks largely to Rozelle's efforts, a Harris poll showed that football had eclipsed baseball as America's most popular spectator sport. Enter Pete Rozelle, 33, who assumed the commissioner post in 1960 and would transform the NFL. By the mid-sixties, thanks largely to Rozelle's efforts, a Harris poll showed that football had eclipsed baseball as America's most popular spectator sport.

As Rozelle's reign began, several disgruntled investors who had been denied NFL expansion franchises—a group mockingly referred to as "The Foolish Club"—joined forces to create the American Football League (AFL). The NFL had withstood earlier threats by rival leagues, but the eight-team AFL—which staked out western territory in Houston, Dallas, Denver, Los Angeles and Oakland—immediately made its mark by signing 75% of the NFL's first-round draft choices in 1960, among them the Heisman Trophy winner Billy Cannon.

Beyond competing for talent, the rival leagues squared off in a battle for television viewers. The NFL "had a problem," Rozelle recalled years later, "because in 1960, when I became commissioner, clubs made their own television contracts, and the small market clubs did not do very well." The AFL moved quickly, landing a contract with ABC worth $2.1 million a year.

Rozelle managed to get a much bigger deal from CBS for $4.65 million, predicated on a new revenue-sharing strategy: Money would be pooled among all NFL teams, essentially guaranteeing them profitability each season before a single pass was thrown. However, a U.S. district court voided the deal on antitrust grounds, forcing Rozelle to seek help on Capitol Hill. What resulted was the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961, giving a professional sports league the right to sell all games of its individual teams as a package, a structure that dramatically changed the business of football.

Today, Rozelle's formula yields annual television revenue of $11.46 billion. According to Nielsen data, among 2023's 100 most-watched TV programs, 93 were NFL games, with the Super Bowl's 115.1 million viewers topping the list.

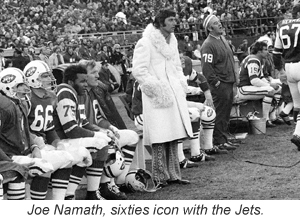

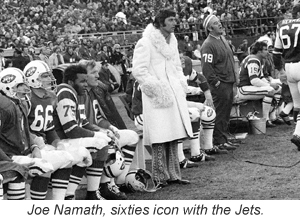

Competition between the NFL and AFL to sign top players brought football into the superstar era, punctuated by the 1965 draft in which Alabama's quarterback, Joe Namath, was selected by the NFL's Cardinals and the AFL's Jets. He signed with the Jets for $427,000, more than double what the Cardinals had offered.

"Broadway" Joe's huge deal reverberates to this day. Last fall quarterback Joe Burrow became the highest paid football player in history, re-signing with the Cincinnati Bengals for an annual average of $55 million.

Another early '60s breakthrough, receiving virtually no publicity but dramatically affecting football's popularity in years to come, occurred in August 1963 during a gathering at the home of Bill Winkenbach, a minority owner of the Oakland Raiders. Frustrated by the Raiders dismal record (they finished 1-13 in '62), "Wink" and his pals fantasized about a game that would allow participants to roster stars from both pro leagues—players like Jim Brown, Mike Ditka and Frank Gifford. So, they invented fantasy football.

The Greater Oakland Professional Pigskin Prognosticators League (GOPPPL) was composed of Raiders staff and local sports writers. They played for pennies (a touchdown was worth 50 cents) but their larger purpose was promotion. GOPPPL's original charter stated, "it is felt that this tournament will automatically increase closer coverage of daily happenings in professional football." GOPPPL continues to this day with Stan Heeb, who joined in 1974, as its commissioner. "Fantasy gives us lay people a vehicle to show our expertise in putting a team together," he told me.

Now played by more than 30 million Americans, fantasy football has grown into an $11 billion business for providers such as DraftKings, FanDuel and Yahoo, as well as the NFL itself. For TV networks and advertisers it is the perfect "glue," holding fans' interest during even the most lopsided games, because in fantasy you root for individual players rather than entire teams. Fantasy paved the way for massively popular legal sports gambling, now available in 38 states.

In 1962, Pete Rozelle created NFL Properties, an umbrella marketing department that would represent all teams with logo jackets and hats, kids lunchboxes and even breakfast cereal. Promotion expanded in 1963 with the opening of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. Two years later, the league took over NFL Films, a unit that became immensely profitable by controlling on-screen content. The sports writer Michael MacCambridge said of NFL Films, "And so began the profligate documentation that would bring about the self-mythologizing of pro football."

Through the first half of the decade a growing number of fans embraced the AFL's style of play that favored passing over the NFL's methodical running game. Off the field, the cost of competing for players was becoming untenable. "The owners on both sides realized something would have to be done," Rozelle reflected later, "or the weaker clubs in both leagues might eventually fail." By June of 1966 a deal was in place for a combined 24-team league that would expand to 28 by 1970—enriching all teams as a result.

The merger required an antitrust exemption that was granted only after Rozelle promised the powerful Louisanna Congressman Hale Boggs an NFL franchise for New Orleans. Legislators also demanded additional stipulations, one of which effectively blocked the NFL from broadcasting games on Friday nights and Saturdays in the fall when high school and college teams usually play.

On January 15, 1967, the rival divisions met for the first time in the AFL-NFL World Championship Game (retroactively named Super Bowl I two years later). The NFL's Packers handily defeated the AFL's Chiefs, 35-10, with live TV coverage provided simultaneously by CBS and NBC. A 30-second commercial cost $37,500; this year a similar length ad is priced at $7 million.

In January 1969, the heavily favored Baltimore Colts met the upstart New York Jets in Super Bowl III. Curt Gowdy, who did the play-by-play on NBC, revealed later, "Pete Rozelle told me there was anxiety that if there were another lopsided game, they'd have to scrap the game or create a new formula for it."

Led by their brash quarterback Joe Namath, who had boldly predicted victory a few days earlier, the Jets managed a remarkable 16-7 victory. After 10 years of turbulence and innovation, professional football's future had come into sight.

(c) Peter Funt. This article originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal.

|

|

Enter Pete Rozelle, 33, who assumed the commissioner post in 1960 and would transform the NFL. By the mid-sixties, thanks largely to Rozelle's efforts, a Harris poll showed that football had eclipsed baseball as America's most popular spectator sport.

Enter Pete Rozelle, 33, who assumed the commissioner post in 1960 and would transform the NFL. By the mid-sixties, thanks largely to Rozelle's efforts, a Harris poll showed that football had eclipsed baseball as America's most popular spectator sport.