| I'm not usually a fan of movies with messages, or of Hollywood's tendency to take liberties with history and then market the resulting drama as "fact-based." However, "Just Mercy" is faithful to the memoir of the same name by Bryan Stevenson, the activist lawyer beautifully portrayed by Jordan. Indeed, the film is so careful with the facts that some critics have complained it lacks dramatic punch.

I disagree, but judge for yourself when the film opens nationwide.

A note at the end of the movie explains: "For every nine people who have been executed in the U.S., one person on death row has been exonerated and released, a shocking rate of error." Stevenson and his colleagues at his nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative have won relief or release for more than 140 death row prisoners.

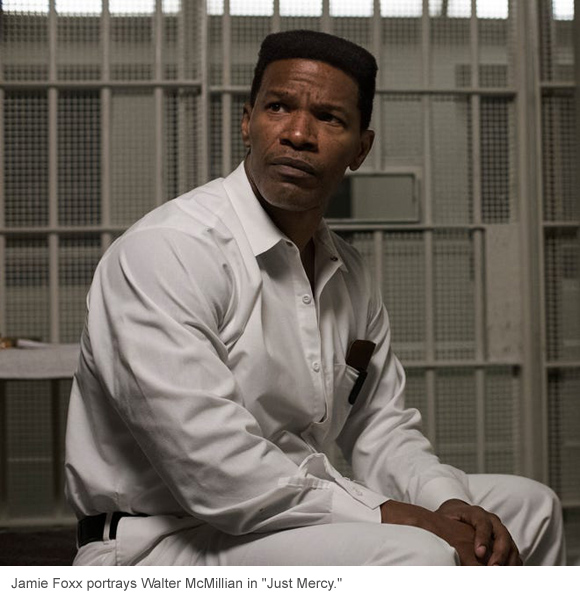

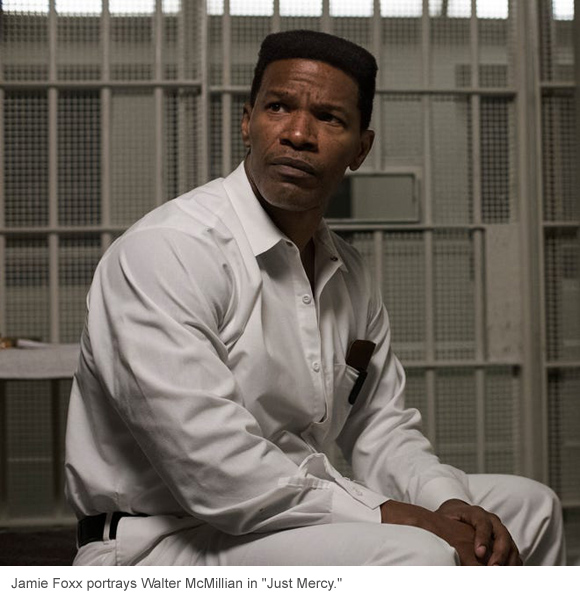

The film uses Stevenson's early career in the 1980s (soon after he earned his law degree from Harvard) as the canvas on which to paint a picture of racial bias in the judicial system and, specifically, in the area where it's profoundly consequential: the death penalty.

My view that capital punishment is immoral is shared by many Americans. But beyond questions of morality are problems of cost and racial bias. While the number of executions in America has dropped in recent years — to a near low of 22 in 2019 — racial bias in capital cases has actually increased.

A recently released study by The Intercept news organization, going back to the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976, concludes that "the death penalty appears to be more racially biased than ever."

In the first decade after capital punishment was reinstated, 46% of those sentenced to die in states that now use the death penalty were people of color. In the 10 years ending in December 2018, the percentage grew to 60.

At the outset of his legal career, Stevenson was shaken by a 1987 Supreme Court decision upholding the death penalty in a Georgia case marked by racial prejudice, he told The Wall Street Journal. Writing for the majority, Justice Lewis Powell deemed the inequities found in Georgia's death penalty sentencing to be "an inevitable part of our criminal justice system."

Last year, New Hampshire became the 21st state to ban capital punishment. California, meanwhile, placed a total moratorium on executions. Public opposition to the death penalty is increasing. On murder convictions, a larger percentage of Americans favor life without parole over the death penalty than ever in recent history, at 60%, according to Gallup.

Yet last summer, the Department of Justice announced, after two decades, that it would resume executions for federal crimes. Attorney General William Barr backed the decision, stating, "We owe it to the victims and their families to carry forward the sentence imposed by our justice system."

Barr chose to overlook the fact that several families of victims in federal cases have spoken out against the death warrants.

Herbert Richardson (played in the film by Rob Morgan), was a Vietnam War vet crippled by post-traumatic stress disorder who conceded his role in an Alabama murder — but his fate in the state's electric chair in 1989 is almost as heart wrenching as if he were innocent.

The execution scene is handled with great reserve by director Destin Daniel Cretton, yet it packs the film's most powerful moral message about capital punishment.

"The death penalty is not about whether people deserve to die for the crimes they commit," Stevenson writes in his memoir. "The real question of capital punishment in this country is, Do we deserve to kill?"

Hollywood has done us a favor by bringing Stevenson's insight and inspiration to the screen. Our politicians and judges should be required to see it.

(c) Peter Funt. This column originally appeared in USA Today.

|